Universitetsavisen

Nørregade 10

1165 København K

Tlf: 35 32 28 98 (mon-thurs)

E-mail: uni-avis@adm.ku.dk

—

Science

Cooperation — The workshop is a key part of the cutting-edge research at the Niels Bohr Institute. It has, perhaps, the best working environment at the University of Copenhagen. And it can solve almost impossible tasks. Now they have finally got the pendulum swinging again

It is buzzing with life again inside the large five-storey rotunda at Geocenter Denmark. And it has done so every time either Dennis Wistisen, Simon Fassel, Clive Ellegaard or Thomas Hedegaard of the Niels Bohr Institute (NBI) Electronics and Mechanics Workshop has been there to fiddle with the big pendulum.

They all helped to get the Foucault pendulum swinging again after almost twenty years of standstill. The University Post was invited to a workshop lunch one Wednesday in April at the Geological Center in Copenhagen.

The Foucault pendulum was created by the French physicist Léon Foucault in 18th-century Paris. It is an instrument that shows how the Earth rotates on its own axis, because the pendulum’s oscillation changes direction in step with the Earth’s rotation. In physics, this is called the Coriolis force. You can still see Foucault’s original pendulum, which has been on display in the Panthéon in Paris since 1851.

We kind of feel like we are on a national team

Dennis Wistisen, head of the NBI workshop

31 years ago, 87-year-old Clive Ellegaard, an associate professor emeritus of physics, helped install a Foucault pendulum at the University of Copenhagen. He was also behind the light installation NBI Colliderscope on the façade of the old Niels Bohr Building on Blegdamsvej.

»I was in charge of the experimental teaching then, so the dean of the Faculty of Science at the time, Henrik Jeppesen, suggested that we should hang a pendulum in the middle of the rotunda for teaching purposes. I thought that was a fun task – and they did too,« says Clive Ellegaard and points to the three from the NBI workshop.

A Foucault pendulum is a delicate instrument that requires maintenance. Just a few micrometres of wear and tear is enough to send it out of its trajectory. In the first decade, Clive Ellegaard was therefore often up on top, changing parts of the bearing so that the pendulum could swing once again.

»Back then, we had to put up a ladder and climb onto the roof of the rotunda to fix the pendulum when it went off kilter. Today, the young people have scaffolding, but we old folks did not have these safety precautions,« says Clive Ellegaard with a smile.

When he retired back in the 2000s, the old pendulum was completely discontinued.

And then there was an episode with a student who jumped up on the pendulum like Miley Cyrus in the Wrecking Ball music video. This is really not recommended, as the steel wire carrying the 130 kilo ball can break.

We are in such close contact with the workshop that you can come up with a pencil drawing and then get something decent out of it

Since then, both foreign tourists and teachers have asked for a restoration of the pendulum. But every time someone wanted to fix it, it came to nothing. Until the spring of 2023. Poul Dyvelkov, an operations employee at the Geocenter, got tired of looking at the thing that did not work.

»So I gave a nudge to John Corell from Campus Service, who found out how to get a grant so that the NBI workshop could take on the task,,« says the operations staffer.

John Corell met up with Dennis Wistisen over a beer at the KU Festival in 2023. Dennis Wistisen is head of the NBI workshop – or as he puts it: team captain.

»I thought it sounded exciting,« says Dennis Wistisen:

»The assignment is especially fun for us because Clive did it back in the day. And it’s in our Niels Bohr Institute DNA that we, of course, have to get it to work. Even though it is also a complex matter.«

Another important part of the Niels Bohr Institute DNA is the community. In the workshop we all work together, so no one is left alone with difficult and costly tasks.

Wistisen told his colleagues about the task shortly afterwards. After an exchange of ideas over lunch, one of the newest employees took it on. Simon Fassel is a trained mechanical engineer, and had only worked in the workshop for about a year before he took on the pendulum task in collaboration with the more seasoned Thomas Hedegaard, who has worked as a research technician at NBI for 16 years.

»Simon was keen on taking on the task and had lots of ideas on how to fix the pendulum. He had just finished his education and was good at thinking a little bit outside the box,« says Dennis Wistisen, before Simon Fassel added:

»It was difficult to figure out what to do about the old bearing in the pendulum without it having to be constantly fixed. One day we got the idea of how to do something completely different, so it didn’t have to be changed all the time.«

The idea that Simon Fassel had stems from the concept of compliant mechanism.

»It’s another way of thinking about mechanical design. Instead of stiffening the parts, the material properties and geometry of them are exploited to achieve a flexible design. By having a frictionless bearing that flexes, we avoid the friction that gradually destroyed the old bearing.«

The new compliance mechanism should last for over 100 years. But the sensitivity of the pendulum requires a number of other interventions.

A magnet is required in the floor, for example, to pull on the 130-kilogram steel ball so that the pendulum does not come to a halt. It is also necessary to have an outer plastic wall that straightens the movement of the pendulum and sends it back in the same direction.

»Without the corrections, a group of passers-by would be enough to shove the pendulum out of its trajectory,« says Clive Ellegaard.

In Paris, there is no magnet, but a custodian whose job it is to keep the pendulum going.

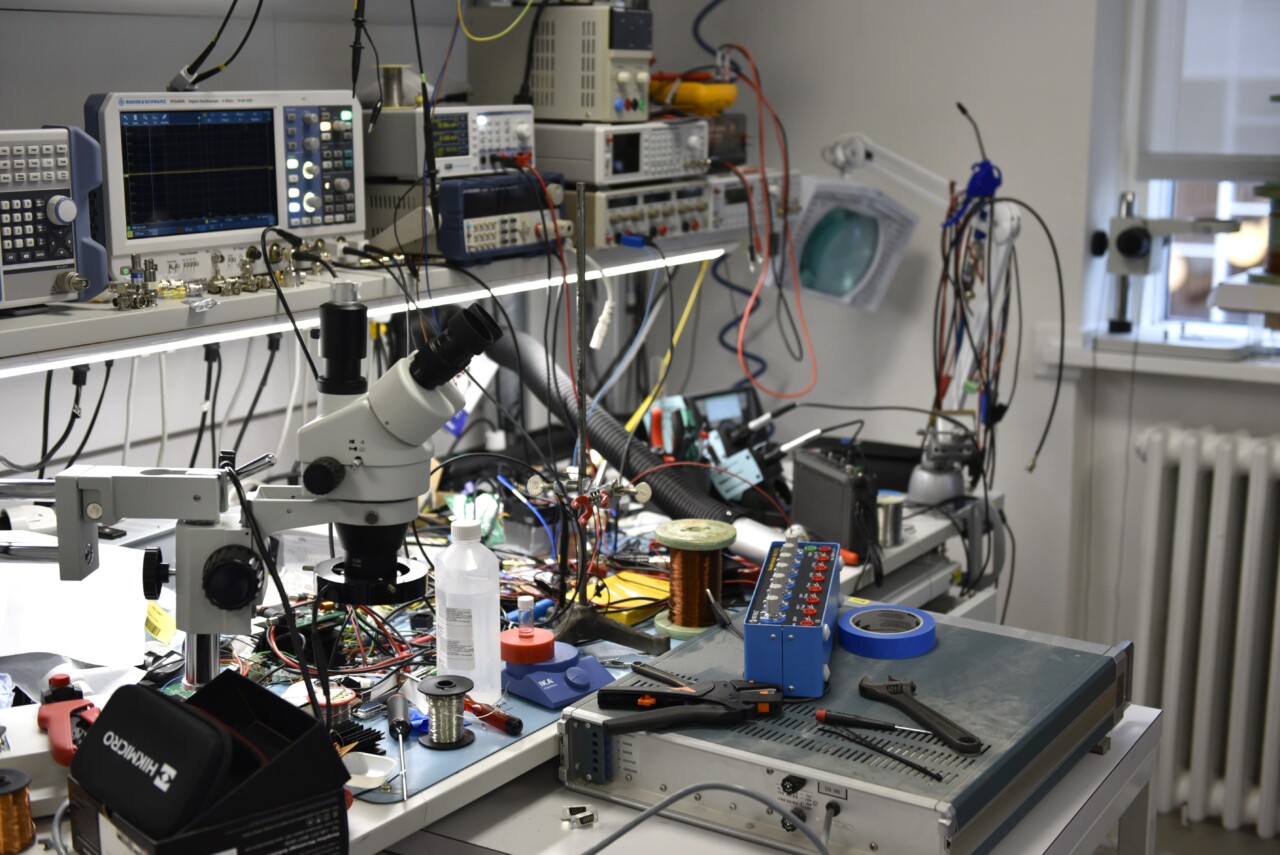

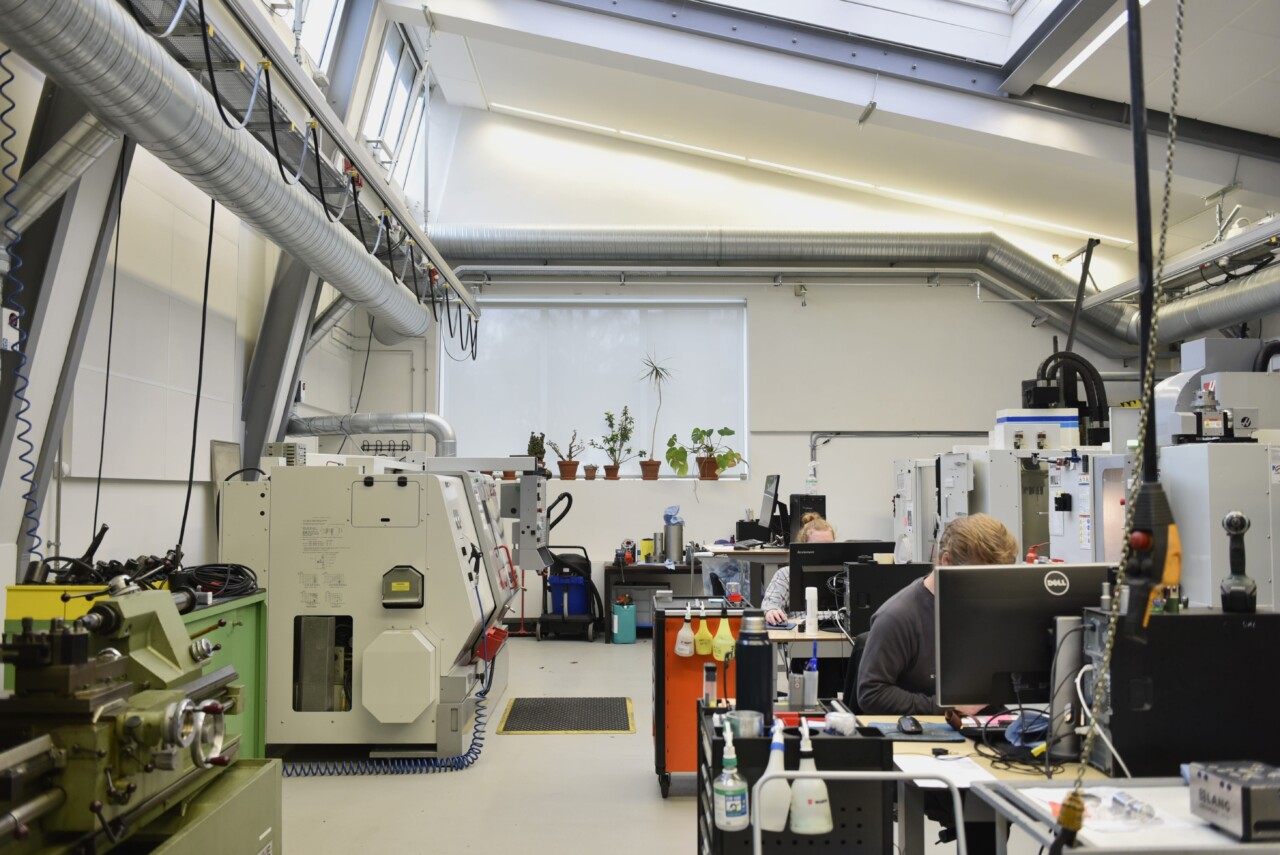

When you enter the workshop in the Universitetsparken campus area, you are greeted with the characteristic smell of oil and coffee. Words like quantum metrology, spectrograph and femtosecond vacuum chamber are everyday words.

The workshop has 18 employees divided into electronics and mechanics.

Creativity, high spirits, and collaboration are still alive and kicking here in spite of centralization, time registration, and financial management.

»We are all extremely happy to be here. And we are humbled that we can be part of cutting-edge research. The projects that we are involved in are at the forefront all the time. Like some fun story in a newspaper or on a television programme where something that we’ve made is driving around Mars. It’s a privilege, and a motivator,« says Dennis Wistisen.

Thomas Hedegaard compares the workshop to a kitchen where the different chefs have different areas of expertise.

»You can do a lot with a knife, but you just can’t do everything. The more tools you have, the more – and the more fun – things you can do.«

When we got the grant, we were asked if it was a work of art. And I said yes

Clive Ellegaard, associate professor emeritus of physics

It has led the technicians to Greenland, China, Chile and CERN in Switzerland. But they are happiest in their daily lives at the workshop, where there is close collaboration with researchers and students, and where the tasks are never the same.

»If you’re in a machine factory, you never meet the end user. Then you’ve just made a gadget you’ve been told to make, without perhaps ever knowing what the gizmo was for. I think that’s the great thing about being here,« says Dennis Wistisen.

The researchers are dependent on the NBI workshop being able to produce the right measuring instruments. But the workshop is also dependent on the researchers’ specific knowledge and wild ideas, says Dennis Wistisen:

»Some of these researchers are world leaders within their fields. So regardless of whether the researchers come from X-ray physics, glaciology, biophysics, astronomy, geophysics or particle physics, we kind of feel like we are part of the national team. Part of something special. This also went for collaboration on the pendulum with Clive.«

»It goes both ways,« says Clive Ellegaard and continues: »We have such close contact with the workshop that you can turn up with a pencil drawing and get something out of it.«

In fact, collaboration between the two sides can become so symbiotic that researchers hardly need to say anything before the engineers and technicians understand the task.

Now the Geocenter’s operations staffer Poul Dyvelkov is pleased that the pendulum is swinging again when he is at work. He is responsible for resurrecting, every morning, the cones that the pendulum has toppled in the past 28 hours and 59 minutes that it takes the pendulum to do a full circle at our latitude. If you put the pendulum at the North Pole, it would take exactly 24 hours, while it would not change direction on the equator at all.

»When the pendulum wasn’t swinging, the rotunda was actually a deserted space. A bit dead. But as soon as the pendulum swings, the room has a function. It’s kind of magical how the pendulum brings the room together as a meditative focal point,« says Dennis Wistisen.

He has invited all the workshop employees to a workshop lunch at the Geocenter to inaugurate the pendulum, and get a well-deserved break after labour-intensive months preparing some equipment for ice core drilling in Greenland.

Hopefully, the pendulum has a long life ahead of it.

The workshop will use the compliance technique in the newly invented bearing in the future. In vacuum systems, for example, where things in ultra-clean environments need to be able to move without human intervention.

In addition, the pendulum is no longer just an instrument, but also an attraction and even a work of art, according to Clive Ellegaard.

When we got the grant, we were asked if it was a work of art. And I said yes,« he says.

This means that the university is now committed to maintaining it as a piece of art. Then we just have to cross your fingers that neither the Geocenter nor Gefion gymnasium parties throw the pendulum off track.