Universitetsavisen

Nørregade 10

1165 København K

Tlf: 35 32 28 98 (mon-thurs)

E-mail: uni-avis@adm.ku.dk

—

Culture

Change — Copenhagen has had a long history with fire. Its architecture, its literature, and its history have gone up in flames on multiple occasions. But, in the wake of the Notre Dame blaze in Paris, we ask what a city can gain from fire?

Just a few weeks have passed since Notre Dame was razed by fire in Paris. France has pledged itself to rebuilding and has already accrued EUR 1 billion in donations. Amid all the questions and controversy, it brings up the historical relationship between cities and fire.

Wildfires are often more restorative than devastating. The same can be said about urban fires.

Cities rebuild, adapt, and learn from fire and nowhere is a better example than Copenhagen. In the less than 80 years between 1728 and 1807 the city went through at least three major fires.

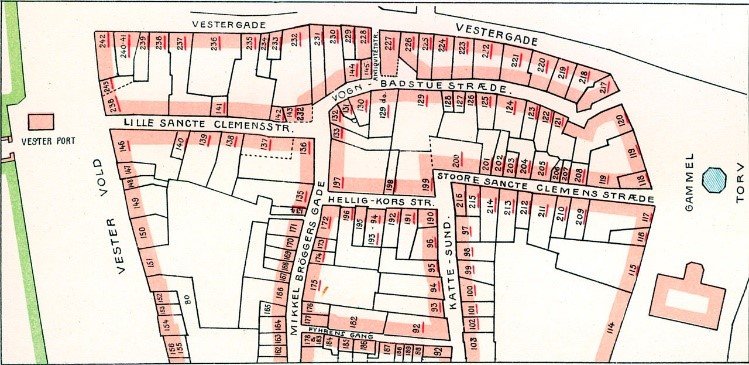

The most infamous of the conflagrations, in 1728, brought on the greatest destruction. Starting on October 20th and burning for nearly three days, almost half of the medieval section of the city was destroyed.

READ ALSO: University of Copenhagen history: The fire of 1728

The cultural loss is immeasurable as many of the city’s main archives, libraries and research facilities were consumed.

Copenhagen, however, survived, and had been mostly rebuilt by 1737, in under ten years. The city seemed determined to avoid the series of unfortunate events which had exacerbated the damage in the fire. Copenhagen had in the 1728 fire been hit by a combination of strong winds, empty water conduits, drunken firefighters and narrow streets.

Many of the improvements they put in place are still observable today.

Firstly, several commissions were established. The Regulation Commission (Reguleringskommissionen) stipulated a widening of the streets to a minimum of ten metres and, although the rule was not fully implemented due to protests from property owners whose land would be shortened as a result, post-fire Copenhagen was noticeably straighter and broader.

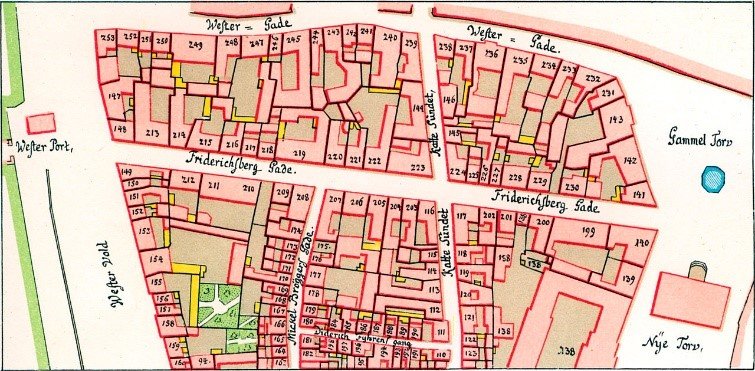

In fact, had it not been for the 1728 fire, Copenhagen would likely not be home to one of Europe’s longest pedestrian streets, Strøget. Part of the effort to uniform the layout, the first half of Strøget, Frederiksberggade was built over the ruins of several medieval alleys.

The city exploited the destruction to implement forward-looking plans and improve circulation. A great example of this is Kultorvet. Today one of central Copenhagen’s main squares, it had been conceived during the post-fire reconstruction.

Another important commission was the Building Commission which banned half-timbered houses. Although this rule was once again undermined by complaints, it also had a substantial effect on the aesthetic of Copenhagen.

For starters, the fire houses (ildebrandshuse), featured today in some of the city’s most picturesque locations like Gråbrødretorv, were designed by Johan Cornelius Krieger as a half-timber, half-brick compromise. The brightly coloured buildings inspired several subsequent houses in Copenhagen.

1728 enthused several other significant movements such as the revival of Pietism. The fire had been seen by many as a punishment by God. A campaign to cleanse the city led to the establishment of orphanages, hospitals and schools.

1728 had also seen the invention of fire insurance. Kjøbenhavns Brandforsikring was the first fire insurance company, establish in 1731 by Hans Henrik Bech and Hans Hansen Berg. It is still around today as part of one of Scandinavia’s leading insurance companies Tryg, which lists the original company as its earliest history.

To some extent, the city took the fire as an impetus. Historian Svend Cedergreen Bech saw the reconstruction period as a blossoming and Copenhagen as a new cosmopolitan world capital.

The 1795 fire was a result of misfortunes that were similar to six decades prior; strong winds, dry timber caused by drought, incompetent firefighters and locked fire hydrants.

Burning for two days, the fire had struck southern Copenhagen, destroying the remaining quarter of the middle-age’s architecture, nearly 50 streets and several prominent churches and castles. This time, however, the city had managed to prevent the fire from spreading North and, crucial to the rebuild, the people had more money.

Importantly for the economy, this strongly influenced the establishment of Denmark’s first mortgage credit institution, Husejernes Kreditkasse, by a group of Copenhagen’s wealthier citizens, which, as part of BRFkredit, remained active until 2014.

The fire had also inspired other major social changes such as the creation of some of Copenhagen’s first storefronts. Sellers had previously been informally selling out of their homes, and the reconstruction period was an opportunity to make their trade more sophisticated.

Stricter building legislation was also implemented. Again, streets were widened and brick was enforced as the mandatory building material. Buildings at the end of streets were now required to be chamfered, with cut away corners which allowed easier access for fire-fighting vehicles. And it is responsible for modern Copenhagen’s openness and the charming octagonal plazas dotted around the city.

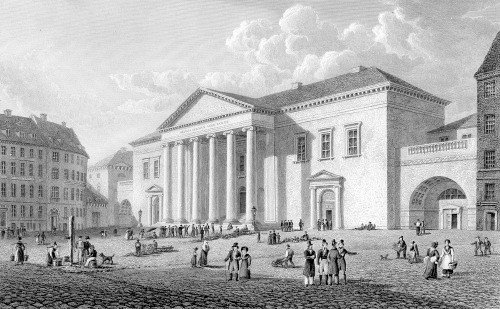

The fire coincided with the Danish Golden Age where neo-classical architecture emerged and thus, 1795 oversaw Copenhagen’s most significant aesthetic transformations. The new style, as seen in some of the city’s most attractive sites, such as Gammeltorv square or the Court House (both rebuilt after the fire), contributed to the atmosphere that modern Copenhagen is unique for.

As art historian Giles Worsley puts it:

»Here [in Copenhagen] we have the quiet street scene that was captured so beautifully and fittingly by the gentle works of the Golden Age. There is no sign of the self-satisfied boasting that is characteristic of the London or Paris of the time.«

With so much of history lost, there was no option but to modernise, and it is the university that embodies this the best.

Destroyed twice, the University of Copenhagen has a long history of resilience and reinvention. Several of the university’s main buildings had to be rebuilt, first after the fire of 1728 and then again after the 1807 bombardment by the British during the Napoleonic Wars.

This included the former library housed in the Trinitatis Church. Despite having lost vast collections of literature, research and irreplaceable equipment, the university is now home to the largest library in the Nordic region, and one of the largest in the world.

The bombardment of 1807 however, had the greatest bearing on the form that the modern University of Copenhagen has now taken. The changes to Frue Plads, where the headquarters of the university is situated, demonstrates this. Rather than rebuilding the cemetery attached to the Church of our lady, the administration took the opportunity to join the surrounding areas and the courtyard was formed.

C.F. Hansen, one of Denmark’s most prolific architects, was assigned the task of redesigning the sector and masterfully employed the same neoclassic style that had been so effective after 1795. His work on The Church of Our Lady, the cathedral which the main building looks out on, is exemplary. The muted interior ceiling, simple classical lines, and Bertel Thorvaldsen sculptures make it different from Europe’s medieval cathedrals and one of Copenhagen’s unique architectural pieces.

Sources

And the University of Copenhagen website.

The university’s impressive main building, had not begun to be rebuilt until 1829 due to financial issues. Slightly rebelling against the classical trend of the time, designed by architect Peder Malling and inaugurated in 1839, the building took on the more imposing gothic style we know today. The reconstruction period seemed to create a catalyst for the university as it followed soon after with several other modernising additions including a new library in 1861 and a zoological museum in 1871.

Naturally, the institutions also saw development. The new growth required funding, and significant financial management reforms were implemented.

Specifically, finances were centralised and with responsibility no longer in the hands of departmental professors, combined with a modernisation of the payroll, the university could now increase its professorship. This history seems to have created a legacy as the university continually challenges itself to reinvent and improve; the most recent construction work at South Campus is emblematic of this.

Ultimately, although painful at first, fire is often part of the lifecycle of a city. In the context of misfortunes like Notre Dame, this concept can be reconciling but it also poses some important societal questions.

What purpose does art, architecture or history play in our lives? At what point do we decide something is worth preserving and at what cost?