Universitetsavisen

Nørregade 10

1165 København K

Tlf: 35 32 28 98 (mon-thurs)

E-mail: uni-avis@adm.ku.dk

—

International

Student blockades — In an attempt to fight corruption, students in Serbia are blockading universities and shutting down roads and bridges with demonstrations. According to a student spokesperson, those in power have responded by paying EUR 50 per beaten-up protester.

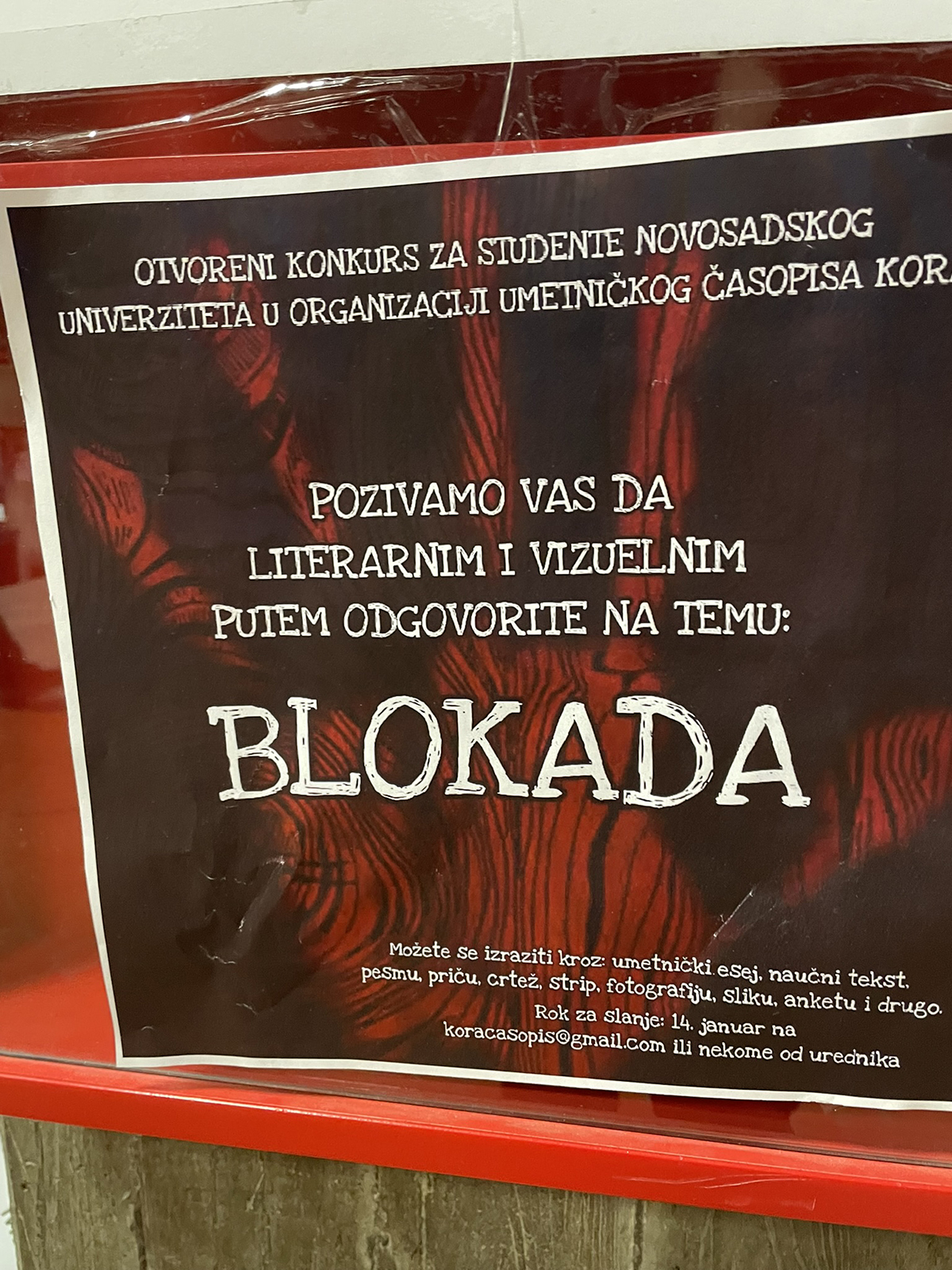

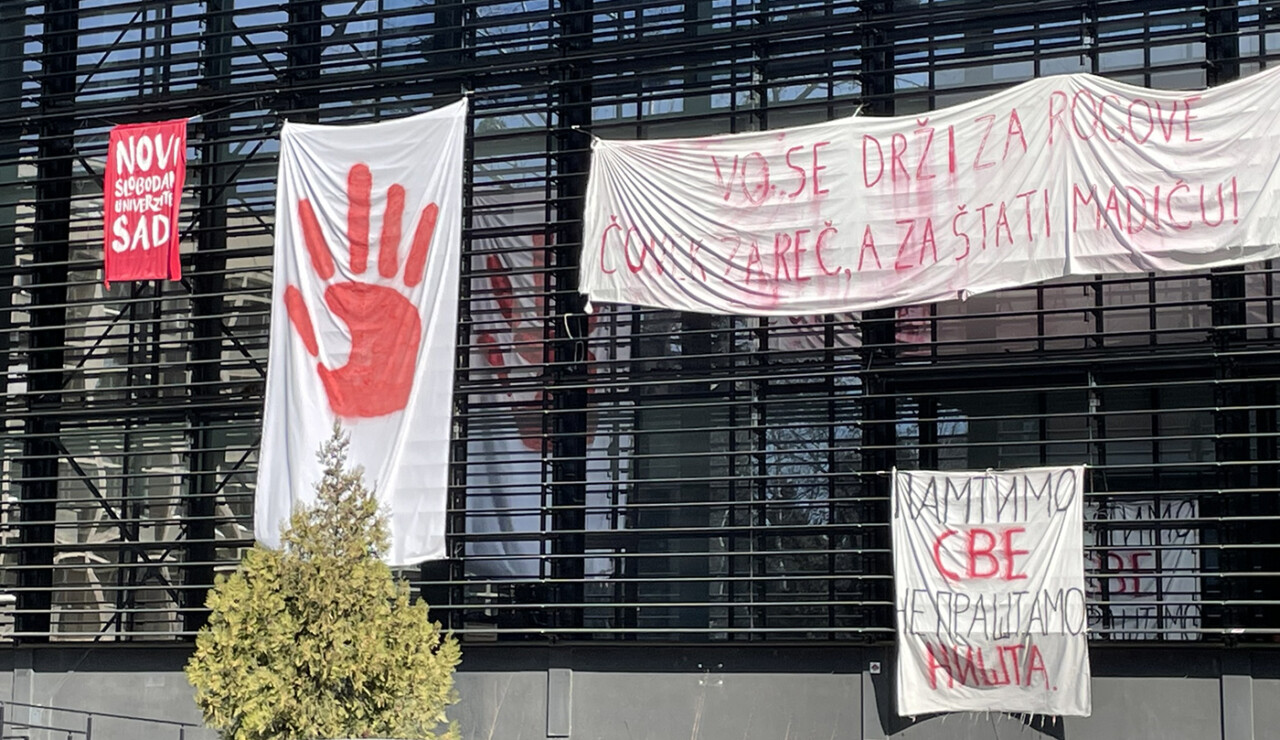

Banners with blood-red hands hang all over the university campus in Serbia’s second-largest city, Novi Sad. The spaces between the concrete-grey buildings are deserted, but at the entrance to the Department of Media Studies at the Faculty of Philosophy, a student sits in front of a computer. She asks for a passport and enters the name before we can gain access to the department.

»We have to do this for security reasons,« explains Anja Stanisavljević from the students’ media group. Her fellow student Nađa Šolaja nods — she herself has been beaten up by people who either support those in power or are simply desperate for money.

»We have been told that the government pays thugs EUR 50 per demonstrator they attack. Some have even been run over,« says Nađa Šolaja, who, like Anja, is part of the media group.

Inside the corridors, mattresses and duvets are scattered around. The students eat and sleep at the department, where teaching has been cancelled. Only occasionally do they go home to take a shower.

On the staircase leading to the first floor stands a Christmas tree. The protests began in November when the roof of the city’s largest train station collapsed. Fifteen people lost their lives, and two remain critically injured in hospital.

»Losing a year of study is a small sacrifice if it means we succeed in creating a better country«

Anja Stanisavljević from the students’ media group

The train station had been under renovation for several years, with construction companies receiving millions of euros for the work. The students believe that the collapse of the roof was due to corruption and are demanding that those responsible for the construction be held accountable in court.

The authorities refused to comply, and so the students took to the streets in protest. They brought with them giant banners featuring blood-red hands.

The protesters were met with pepper spray and arrests, but the demonstrations continued. At the beginning of December, the students occupied the university and blockaded teaching activities, receiving support from many of their lecturers.

»Not everyone supports us — this applies to both lecturers and students — and this is fine, there should be space for all opinions,« emphasises Anja Stanisavljević.

In a classroom, chairs and tables have been pushed to the side, allowing space on the floor for the painting of large banners. On the tables, paintbrushes and spray cans are lined up next to megaphones.

»We are receiving support from more and more ordinary Serbians,« says Anja Stanisavljević. »They help us with free printing of leaflets, technical equipment, and so on.«

She leads the way to an ice-cold back entrance.

»This is our fridge,« she smiles, pointing to shelves filled with fruit, grains, and other food items donated by the city’s residents.

A fellow student walks past carrying a pot of food but declines to participate in the interview.

»The government is trying to infiltrate us, which is why only members of the media group come forward with their names and pictures,« explains Anja Stanisavljević.

Observers say that, in the beginning, the Serbian government and president did not take the students seriously and had not anticipated the level of public support they would receive. But the opposition to those in power has grown significantly.

»It is completely unexpected. There was an assumption that this generation of young people was politically disengaged and passive. But that was a mistake!,« says Tihomir Loza. He is a journalist and the executive director of SEENPM, a network of 19 media centres and institutes in Central and Southeastern Europe, and a long-time observer of developments in the Balkans.

Students from the university in the capital, Belgrade, recently walked 100 kilometres to join the protests in Novi Sad. Along the way, they passed through several villages whose residents typically support the ruling party, but the locals came out to offer the young demonstrators food.

When the demonstration ended and the students needed to return, a queue of taxis from Belgrade was waiting to give them a free ride back to the capital.

Anja Stanisavljević is in her fourth year of studies and could, under normal circumstances, be looking forward to graduation. She is pale but determined, shrugging with a small smile.

»I think losing a year of study is a small sacrifice if it means we succeed in creating a better country without corruption. All we really want is to live peacefully in a law-governed society,« she says.

»I love young people!«

Elderly, anonymous man on the street

The students have deliberately avoided affiliating with any political parties and do not want opposition politicians at their demonstrations.

»We simply want those responsible for the station’s construction to be held accountable and those who have attacked demonstrators to be arrested,« says Anja Stanisavljević.

At the beginning of February, the students appeared to have achieved a major victory when the mayor of Novi Sad and the head of government both formally stepped down. But this has not stopped the protests.

»In reality, they still hold power — no one new has taken over,« says the spokesperson for the media group.

The authorities continue to suppress the protestsl. The demonstrations, for example, get very little coverage in government-controlled media. But now, the blood-red hands can be seen everywhere — on walls and banners along the heavily trafficked main roads of the capital, Belgrade.

»More and more people are joining us. The professional association of lawyers has gone on strike, farmers are helping to block roads with their tractors, and families with children are also taking part in the demonstrations. Even the elderly, who traditionally believed everything the government and president said, are starting to support us. Many of them know some of us young people personally, and now they are beginning to believe in us,« says Anja Stanisavljević.

Her own grandparents have attended a demonstration because they trust their granddaughter’s analysis.

Before the current president, Aleksandar Vučić, came to power, Serbia was ruled for years by the dictator Slobodan Milošević.

The student movement does not have a single leader.

»This is our way of showing the world that there are other ways to lead than the way our country has traditionally been governed,« says Anja Stanisavljević.

The students dream of a fundamental systemic change, built from the ground up. They want to put an end to »the rot that has once again cost Serbian lives« and demand transparency in decision-making processes. Every day, they hold 15 minutes of silence — one for each of the 15 victims.

In front of the now-closed train station in Novi Sad, there are flowers, children’s drawings, teddy bears, and pictures of a child who is no longer alive. A woman hurries past on her way from the bus, which has replaced the trains. She kneels before the flowers and makes the sign of the cross before rushing on.

On the pavement a few hundred metres from the train station, an elderly man stands. He will not say whether he supports the students or not, but he smiles a toothless smile and says:

»I love young people!«

On Saturday, 1 March, young people will once again take to the streets — alongside farmers, families with children, grandparents, lawyers, taxi drivers, and many more who want change in Serbia.