Universitetsavisen

Nørregade 10

1165 København K

Tlf: 35 32 28 98 (mon-thurs)

E-mail: uni-avis@adm.ku.dk

—

Culture

Special exhibition — The exhibition ‘Neanderthals’ at the Natural History Museum of Denmark rejects the idea that the Neanderthals extinction was due to some kind of defect in their intellectual abilities. And the exhibition offers an archaeological sensation.

Try to imagine that a Neanderthal unexpectedly turned up in parliament and addressed the politicians there:

»We Neanderthals did not know 40,000 years ago that we were about to become extinct. You, on the other hand, have the knowledge and the opportunity to avoid the same disaster that happened to us. So why don’t you think about this, before your time is up?«

This is the message that museum director Peter C. Kjærgaard is trying to convey in the exhibition ‘Neanderthals’ at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

»The Neanderthals are our closest extinct relative. Technically, culturally, and in human terms, they had the same skills and knowledge as we had. And we can therefore use the Neanderthals as a reflection of ourselves, our community, and our relationship with nature and global warming. Because Neanderthals were challenged by climate change, just like we are,« says Peter C. Kjærgaard, Professor of Evolutionary History at the University of Copenhagen.

There is nothing to suggest Homo Sapiens wiped them out.

Peter C. Kjærgaard, museum director

Together with his staff at the Natural History Museum, he has focused on giving guests to the museum an understanding of how much we have in common with them. They live on, literally, within us:

»We had viable children with each other, so our genetic material contains up to approximately two per cent Neanderthal genes, and while there were a maximum of a few hundred thousand Neanderthals in the world at the same time, we are almost eight billion homo sapiens today. In this way, there is now more active genetic material from the Neanderthals within us, than at the time when they lived,« says Peter C. Kjærgaard.

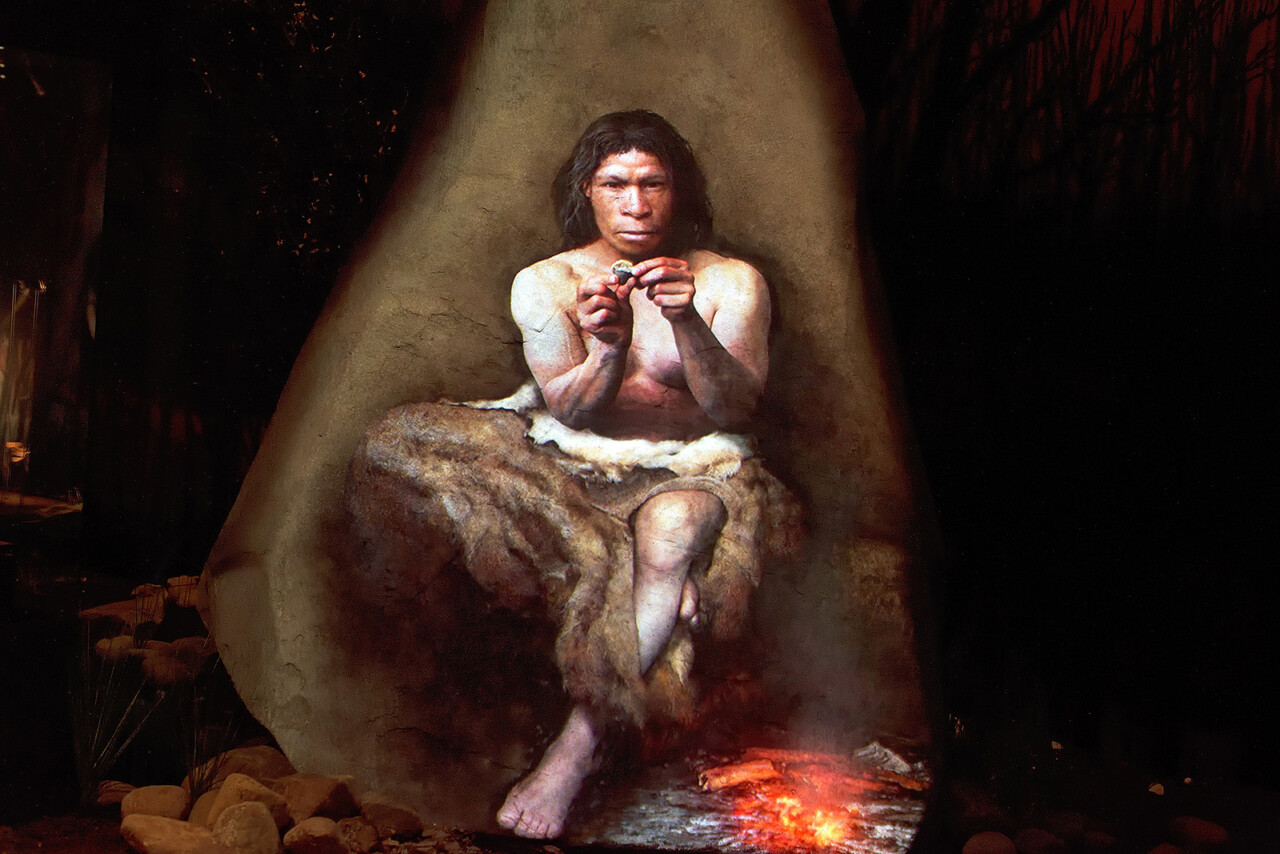

The museum’s largest room is full of large images of Neanderthals , showing us how they lived together. They are depicted in different social situations, like sitting around fires. You can also hear sounds from children’s play and laughter, hammer blows from stone tools, and animal sounds as you move around.

One part of the exhibition shows us that the Neanderthals were so technically advanced that they could produce birch tar. This was used as a strong glue for hunting tools. Birch tar sounds like a relatively simple thing to produce, but it is not. You need to heat up birch bark to a certain temperature to release the tar.

No air — or oxygen — can interfere with the process. This means that the heating has to be done in a closed space. You may well wonder how the Neanderthals knew about this, and how they were able to solve this challenge.

There is also a large room with skeletons from two of the animals most frequently associated with the Neanderthals: The big, strong, and fearsome cave bear, as well as the even bigger, and even stronger, mammoth, which was important hunting game for the Neanderthals.

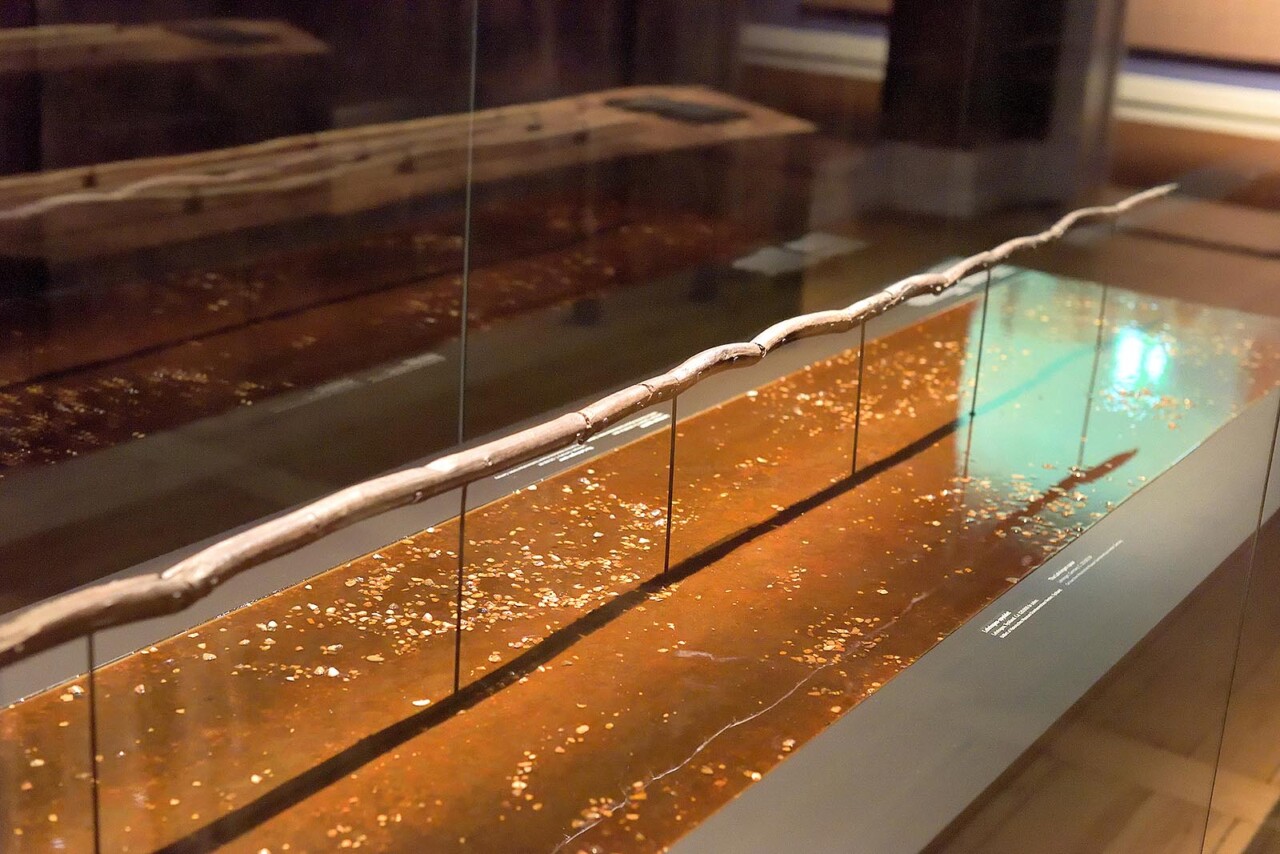

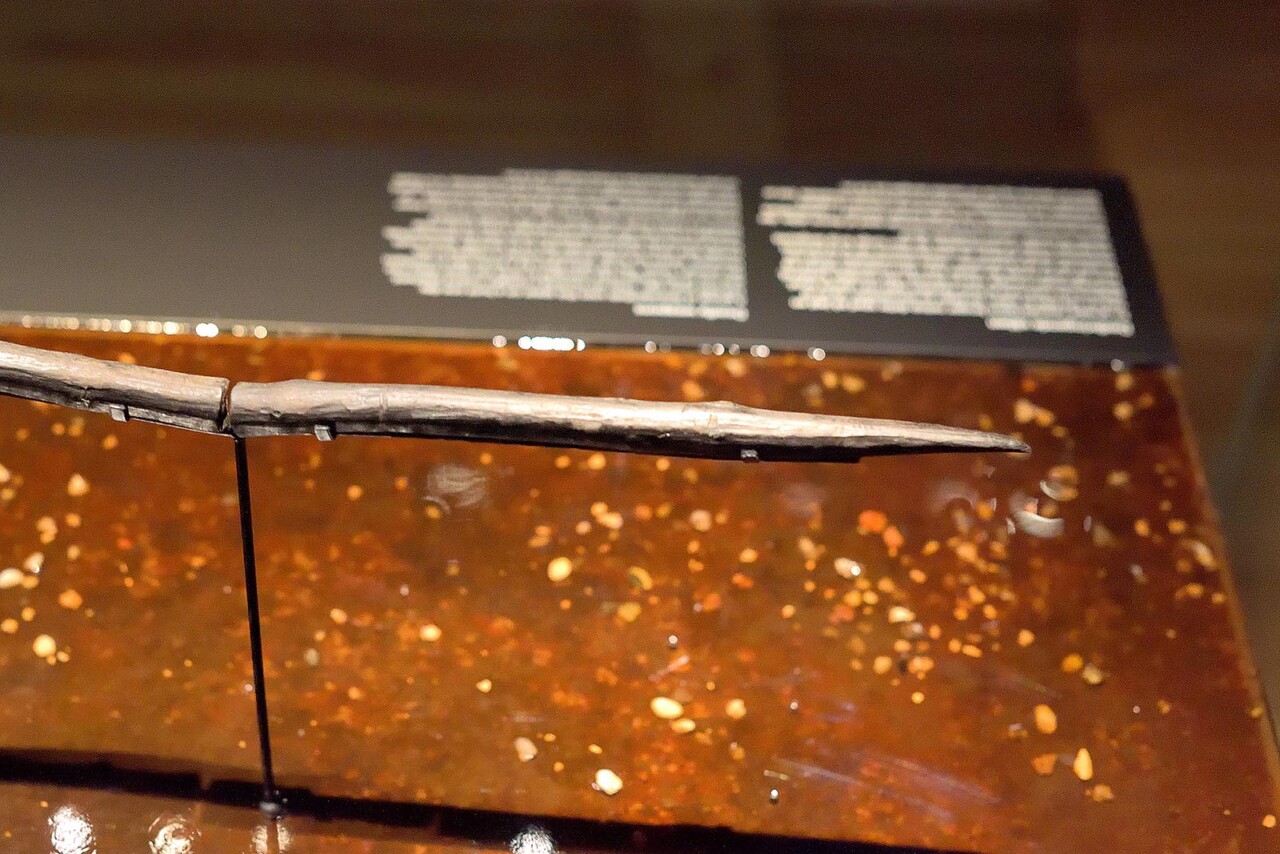

The most spectacular object of the exhibition is in the very first room. A 2.4 metre long spear of wood in a large showcase. The spear is an archaeological sensation.

»This spear is one of the most incredible Neanderthal finds we have. It is 120,000 years old and is almost completely preserved. The spear is one out of only ten that we have found from the Neanderthals,« says Peter C. Kjærsgaard and continues:

»What is even more exciting is that we found the spear in the chest of a straight-tusked elephant along with some Neanderthal stone tools. This has made it possible for us to recreate a hunting scene: The elephant was chased into a bog where it had the spear drilled into it by a Neanderthal. It then started to slowly descend into the mire. But before it finally disappeared, the hunters cut pieces of meat from it to carry away and eat. We can see the cutting marks on the bones from the use of sharp flint tools.«

It is 166 years since the skeleton of the first Neanderthal emerged from the ground in Germany. For a long time, science thought that the Neanderthals were an evolutionary dead end, and that it was therefore doomed to extinction. The neanderthals were assumed to be primitive. This has turned out to be completely wrong.

The Neanderthals interacted with us for 14,000 years

Neanderthals emerged about 450,000 years ago in Eurasia. They repeatedly met humans of the Homo Sapiens type. The two human species lived side by side in Europe for about 14,000 years, from the time the first Homo Sapiens appeared there 54,000 years ago, until the Neanderthals went extinct 40,000 years ago.

The exhibition does not offer a direct answer to why the Neanderthals died out. But Peter C. Kjærgaard offers his own conjecture about happened in the entire region where Neanderthals lived — an area stretching from Spain and the Atlantic in the west to the Caucasian mountains and Siberia in the east.

Peter C. Kjærgaard has, as a researcher, now been given the chance to answer this question, because the sciences relating to the Neanderthals have become interdisciplinary within the last few decades. It used to be mainly archaeologists and palaeontologists who did research on the Neanderthals, and they were only peripherally concerned with trends in nature, climate, and population migrations. This has changed through the collaboration with other branches of science, leading to new knowledge.

»The huge region where the Neanderthals’ preferred hunting game thrived was originally covered by woodlands. But several climate changes changed the landscape completely. The ice grew and then receded, covered, and then laid waste to areas and destroyed the forests. The entire area gradually became a huge steppe about 85,000 years ago,« says Peter C. Kjærgaard and continues:

»But it is important to understand that it was not one single factor that caused the Neanderthals to become extinct, even though the steppe landscape may have made life harder for the Neanderthals so that it ended up pushing down population levels over many thousands of years. There is nothing to suggest that Homo Sapiens wiped them out systematically,« says Peter C. Kjærgaard.

A particular problem for Neanderthals has been that their bodies were designed by nature to need more energy than Homo Sapiens. This led them to concentrate primarily on acquiring lots of meat filled with energy-rich fats and proteins.

This may have been their Achilles heel. Humans of the Homo Sapiens variety can live on a much more varied diet that, in addition to meat, can also come from roots, fruits, nuts, berries and seeds. These things are found in the open steppe landscape. A landscape that, conversely, does not offer the best living conditions for large prey which were the main ingredients in the Neanderthal’s more monotonous diet.

»We know that as individuals are put on existential pressure, the more their fertility decreases. This applies to both animals and humans. We also know that the Neanderthals were increasingly dispersed into smaller groups until 45,000 years ago, when they finally lived in such small groups, and so far apart, that they were no longer genetically viable. There may well have been a competitive element relative to Homo Sapiens, but this was not because they made war upon each other. It has only been a result of the two human species using the same resources,« says Peter C. Kjærgaard.