Universitetsavisen

Nørregade 10

1165 København K

Tlf: 35 32 28 98 (mon-thurs)

E-mail: uni-avis@adm.ku.dk

—

Campus

Reportage — One University of Copenhagen department can be found in the village of Nødebo by the lake Esrum Sø, where Gribskov forest serves as a backyard. The beautiful surroundings are not your typical campus grounds.

If you’re after a job that takes you beyond the constricting four walls of an office, the role of forest worker may appeal.

Think about it. Buzzing insects and rustling leaves, high on oxygen and with a sun-tinged beard (imagine that you have a beard if you don’t), you stretch your arms out wide and look up and down and two the side. Take a sip of iced coffee from your thermos. There’s a little spray can in your belt to spray circles onto trees that someone planted four generations ago. Now they have to come down. You know how to do it.

You have been given responsibility for forming the landscape’s next 100 years.

Brian Dalskov Kristensen, tutor in the forest and nature management program at the University of Copenhagen School of Forestry, says that forestry life attracts many people who have tried out other opportunities and weighed up their choices. Cool-headed people, in other words.

But a fair share of them also get scared away. Forestry work is not just romantic, but also challenging and strenuous.

When Dalskov Kristensen drives us out to the spot in the forest which will serve as today’s classroom, we pass a group of brand new students, men and women. They are sweating, even though it is not yet 10am and the summer heat has not set in yet. The teachers have put them to chopping a load of firewood. They are being tested a little.

Further into Gribskov, three young men are cutting down trees to create a new pathway through the forest. Anders Lund Jensen, a forest and nature management student, points out where the line is to be drawn.

The aim is to get the dogs and mountain bike cyclists to choose a route that runs around a ditch, cuts through the forest and which was once part of a large-scale infrastructure project which began in the Middle Ages, in order to channel water from lakes and streams into the lake Fredriksborg Slotsø.

Sometimes the forest workers let some trunks lie, so that they discreetly block traffic until visitors find another route which does not tread on memories from times long past.

Swedish war captives used to dig in this forest, but the canal system has always functioned well, say historians.

Line Kragelund, 24 years old, comes from Holstebro where her family grows Christmas trees. She is studying forestry and nature engineering and has a room in the collegium at The School of Forestry, a few metres from where she studies. The further from campus you come from, the higher the chance of getting in to a room at the school. There is a fight for them.

It is understandable why they are so highly sought after. Two students, one tall and one short, brush past with towels around their necks and bare stomachs. They have been down to the lake for a morning dip.

Ahead, one of the collegium inhabitants is holding an elegant 30-40 year old bicycle.

“It could be a hopi bike,” says Line. A hopi is a student from garden and park engineering. Line says that hopi boys wear dirty trousers and hopi girls wear flowery dresses – they are often young people from Copenhagen, forest hipsters, if you will. Even in a little student milieu out in the forest, you can find student subcultures.

You can also be a naku or a slinger, says Line. “Now I need to be careful with what I say, but a naku is when you go around with a nose piercing, huge dreadlocks and those kinds of things. They are the resident games organizers, who always have a smile on their face.”

Nakus are nature and culture students from Copenhagen’s technical school, but they also study at The School of Forestry.

As a student of forest and landscape engineering, Line herself is a slinger. That means you wear Fjallraven pants or shorts, leather boots and perhaps a tweed cap. “This is the forestry uniform” she says. “My family are the kind of people who go on hiking trips around Denmark.”

Earlier in the spring, a flock of these students took a hiking trip around Esrum Sø, approximately 30 kilometres.

Forest and agriculture employees have traditionally been forest rangers, but today they find work in many different places. Even Kragelund will soon take up an internship at the National Park in Thy, where her tasks will include taking care of a rare, dwarf bush populating the area. She has arranged the one-year internship herself.

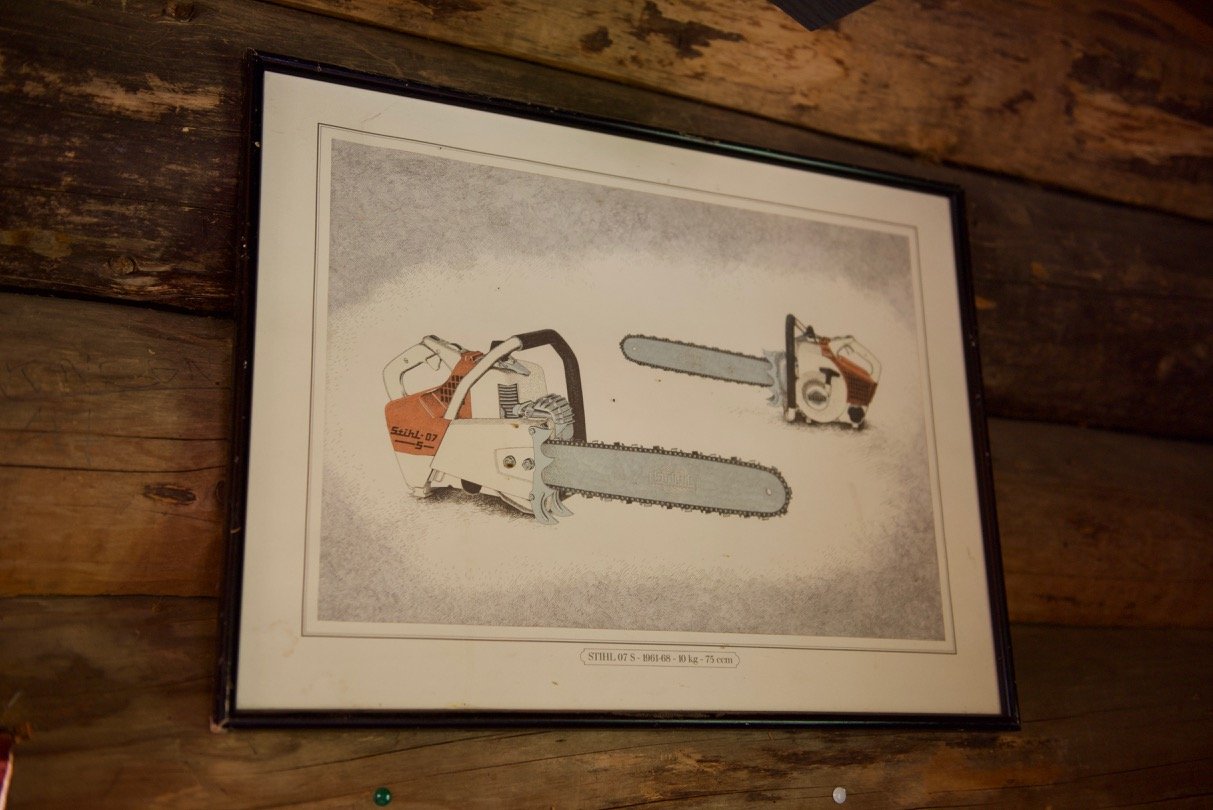

Kragelund says that she likes the program’s combination of theoretical courses – for example business economics or tree biology – and the practical work in the forest. Even though forest rangers do not typically carry out the hard work – they manage and outsource – the students must also understand how to use a chainsaw. “You have to go and learn how it feels on your body,” says Line.

With knowledge comes increased interest in the forest and landscape.

“Before I began here, I thought that the beech forest near where I grew up was really beautiful. Today, I see it with completely different eyes. A walk through the forest suddenly takes twice as long, and you get a crick in the neck from looking up and down and all around – you get a little environmental damage,” she says.

The academic year is bookended by a spring festival and an autumn party.

Students raise their own money for the annual student trip. One fundraising activity is hosting a Christmas market at The School of Forestry that is open to the public.

Forestry is not just a trade. It is political.

“Climate challenges must be resolved by reducing the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, says principal of The School of Forestry, Thomas Færgeman. “And the best way to achieve that is by growing the forest and taking the tree you get and building something out of it, or using it for energy and CO2 storage.”

Færgeman is an agronomist and industry journalist by education. The environment is the common thread, he says of a career which spans positions such as the head of nature and environmental policy at the Danish Society for Nature Conservation, climate journalisim and for six years, director of think tank Concito, which he founded together with politician Martin Lidegaard.

Management of The School of Forestry is a nice extension of such a career, says Færgeman. His students will end up working in a field which will be critical for the future of the planet.

However, the school is also marked by pragmatism. It needs to make money.

The School of Forestry is dependent on the taximeter earnings as well as students, which are the primary income source. In 2017, the school carried out dismissals because the rules for study places were changed so that The School of Forestry suddenly could only accept trade students which had already engaged in an apprenticeship agreement with a company, which is not tradition.

In practice, the rule change sent the majority of accepted students into vocational study, but instead the school can generate earnings by selling its AMU courses better and developing course activities – for example, inviting groups of UCPH’s approximately 10,000 employees to Nødebo for team building exercises or meetings.

“We are at the very practice-oriented and business-oriented end of the scale,” says Færgeman. “The more academic aspects of forestry operations are found in our parallel institute in Frederiksberg, where you find landscape architects and aspiring Ph.ds.”

The influence of more theory based UCPH academia is most seen in the teaching,” says Færgeman. “The good researchers in Frederiksberg often come up here and teach. Many of them have days both places,” he says.

“That man walking past, Rasmus Brodersen, is the head of 45 employees at the Knowledge Center for Forestry and Nature, including PhD’s and professors. He is a forestry worker and today is in charge of employees such as a professor of forest growth that we have up here. This is probably the only place in UCPH where a tradesperson is the boss of a professor.”

In its promotional material, The School of Forestry states that it educates the entire spectrum from “vocational to PhD’s” – meaning everyone from tradespeople to researchers and everything in between.

“I believe that is an enormous strength, that you have the entire palette covered within a relatively little sector, and that it is unusual within the education sector,” says Færgeman.

The statistics also indicate that this offers inspiration when young people from different backgrounds and education work together closely.

“Every year, 10 – 15 percent of the vocational students progress to a forestry and landscape engineering degree, and each year 10 – 15 percent of forestry and landscape engineering students take further studies in Frederiksberg,” says Færgeman.

The same applies to garden and park engineers and nature and culture students.

All images: Christoffer Zieler.