Universitetsavisen

Nørregade 10

1165 København K

Tlf: 35 32 28 98 (mon-thurs)

E-mail: uni-avis@adm.ku.dk

—

Campus

Anniversary — Poor old student rebellion. Its victories are about to end up as defeats for the university today, and its best thinking has been forgotten. And where can you find a living ‘68er’, when today's students are under such pressure?

It is the 50 year anniversary of the student uprising in 1968, but it will no be marked at the University of Copenhagen.

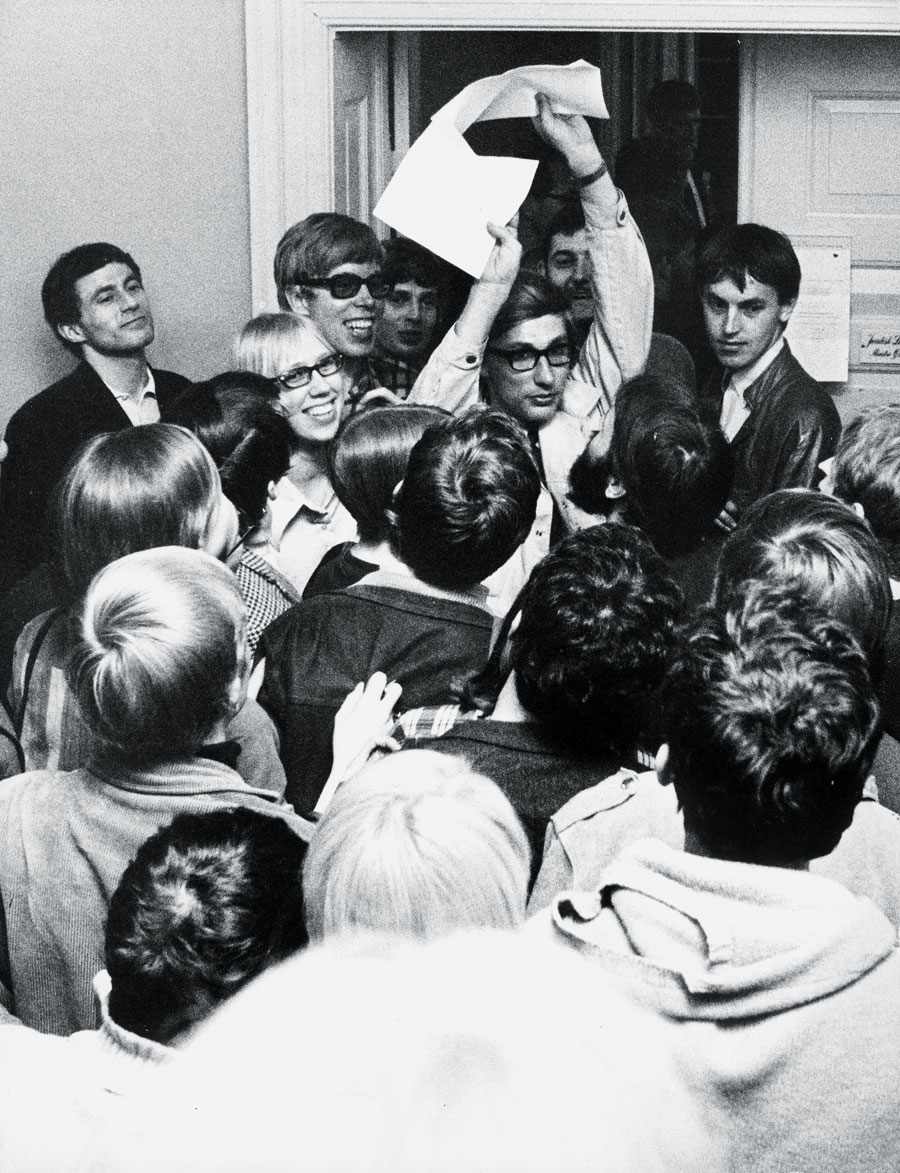

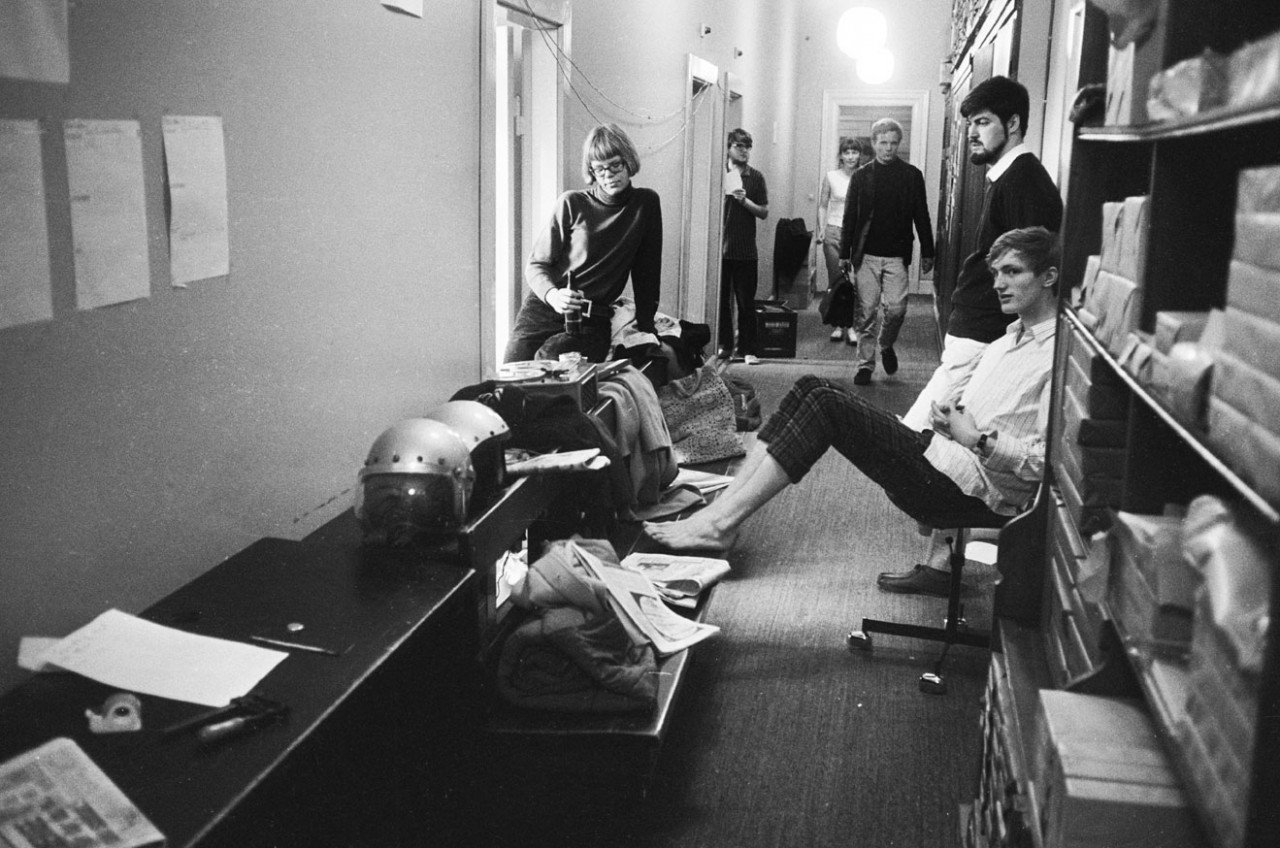

Yes, sure, there will be some pictures on SoMe, they tell us in the communication department, but UCPH, the centre of Denmark during this great time of change, is not, in any way, going all-in as it did so ten years ago. Back in 2008, the university organised a huge ’68-er’ conference, and a website was set up for the period’s core events such as the dissolution of the professors’ regime in 1968, the students’ takeover of the podium at the university’s annual celebration the same year, and the occupation in 1970 of Rector Mogens Fog’s office. The whole package, so to speak.

The people who, now quite old, radically changed society and culture, had their exploits subsequently consecrated when they got into power. Today, the generation of ‘68 is looking tired, and if you believe a study published in the newspaper Politiken, they have largely left their youthful policy ideas behind.

In ironic, but more and more bitter speeches about the period, the Student Council chairman from 1968, Christian Nissen, has described how the top student politicians at the time, rather than being incensed by a real political awakening, used the spirit of the rebellion to promote their own Influence. Just like the MeToo movement today, which has opened up new avenues to power that can be exploited by others, so the student elite of the time merely rode the wave of protest. And this even though they, at the start, risked being overwhelmed.

“The rebellion was just as much directed at me as against the professors. When we changed direction in the Student Council, it was not least for tactical reasons, so we would not be overrun. This, I think, is the way many of us felt. We were not particularly left-wing, but we wanted influence, Nissen said in March this year to the Danish news site Politiken.

Rather than a cause for celebration, 1968 is, according to several observers, an opportunity to mourn what went wrong with the university of today. Not least for the students.

‘Raving lunacy,’ is the expression that Ralf Hemmingsen (born 1949) used about a current proposal from a committee under the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science led by Department Head Agnete Gersing. It wants to strip the power of the study boards that were a direct consequence of the student rebellion, where students were given authority in the creation of their own education programmes.

Gersing argues that the present study boards make for “unclear management responsibility,” which is “a mess”. Their abolishment is a practical solution. And even for the benefit of the students themselves,” she says:

“I think it is in the interests of students that the responsibility for the quality of education is clearly with management, because it simply makes it easier for management to deal with it,” she said to the news site RUC Paper.

Ralf Hemmingsen, who was rector of the University of Copenhagen 2005-2017, and who has now returned to a position as professor of psychiatry, became a student at the age of 18 in 1968. He was therefore too young to participate in the university rebellion. But he understood the breadth and resonance of the movement, and he has written about how he in the summer of 68 saw with his own eyes in Paris how the authorities, after the street battles during the so-called May rebellion, paved the cobbled streets to prevent young people from tearing up cobbles to throw in anticipated new conflicts.

Ralf Hemmingsen says that the proposal for new, hamstringed, study boards at Danish universities demonstrates how things are moving in the wrong direction.

The students of 19-20 years of age who go to UCPH are on their way to becoming pillars of the community in later life. And it is raving lunacy by means of authority to take their otherwise gifted contributions to their own daily lives away from them, marginalising them in a consultative role

Ralf Hemmingsen, former rector at UCPH

“There was a lot of talk of repressive tolerance then, that is, by dealing with the uprising by accommodating parts of it. Today, however, the system is purely repressive. I am not talking about university management, of which I was a part. But today we have a situation where some of the values that can be extracted from 68, and which I consider to be positive, are under pressure. This is the idea of a decentralised space to manoeuvre. That is to say that people who have come together to do something in their local community, in a study programme or at an educational institution, have considerable freedom to organise the tasks themselves. It may sound trite to mention this, but what is it that the emerging Asian societies are interested in, in Denmark? It is the short distance to power, and the personal space of manoeuvrability.”

“I fear that the balance has been tipped in favour of a monolithic, model-economic approach to governance – the policy of necessity. This can be specifically seen in the government’s proposal to hamstring the study boards at universities,” he says.

The students of 19-20 years of age who go to UCPH are on their way to becoming pillars of the community in later life. And it is raving lunacy by means of authority to take their otherwise gifted contributions to their own daily lives away from them, marginalising them in a consultative role. »It is

The former Rector of UCPH was himself criticized for representing the age’s top-down management. But few will argue that Ralf Hemmingsen did not, as rector, fight formidable struggles on behalf of his and (with varying degrees of unity) other Danish universities against The Man: Different governments’ ongoing efforts to take control of academia. And on the question of the power of the study boards, there is perfect harmony between the former rector and the leader of the students today.

The spirit of the times is very much against the students. We are going through paralysing reforms such as the Study Progress Reform, which is extinguishing some of the commitment that exists on campus. If you put people in a rat race against themselves, you paralyze them.

Sana Mahin Doost, Chairman of the Union of Danish Students (DSF)

Sana Mahin Doost (born 1994), is chairman of the National Union of Danish Students, and calls the study boards the ‘ultimate symbol’ of what the 68’ers achieved. She says that the wish of the department head Gersing to take away the power of the students is a

“We brought dominoes with us to show that democracy is falling brick by brick. It all started in 1992, when they started to give more power to rector and curtail the collegial bodies. Then the big 2003 reform with external boards and hired rectors, and most recently in 2017 the appointment of the chairmen of the boards was put closer to the ministry. We fear that 2018 will be the year in which they make the showdown with the study boards.”

The demo took place under the banner of ‘68, “break down the regime of the professors – we want our say, now,” but with the twist that the professor’s regime has been replaced with the “minister’s regime”. As is typical for these kinds of actions, the students were given a friendly reception by the minister and other senior elected representatives.

“They take a look, and then they smile and say that it should be up to the universities themselves how students should be involved. But that it would be foolish for them not to listen to us. They tread water,” says Sana Mahi Doost.

She laughs when the University Post asks whether this was repressive tolerance. But the cold facts are, that the rebellion of 68 resulted in legislation that met the students’ desire for participation, it is difficult to see where the students would find political support today.

“The spirit of the times is very much against the students. We are going through paralysing reforms such as the Study Progress Reform, which is extinguishing some of the commitment that exists on campus. If you put people in a rat race against themselves, you paralyze them. The professors’ regime from before 1968 was deeply problematic, but there was, after all, a professional basis behind what the professors said. Today, it is not even the ministers who manage anymore, but the civil service. But despite these things, we are still able to mobilise.”

That is a fair point. In March 2018 the student movement managed to provide sufficient signatures to get the Danish parliament vote on the country’s first citizens’ proposal to abolish the cap on education that prevents young people from switching education programmes. In advance, however, the key political parties spokesmen had announced that they did not even intend to consider rethinking their previous policy.

“Commitment from students is challenged by an anti-youth policy. We are a small youth generation, that can easily be run over. They promise us tax relief when we get older, but there is no guarantee for this – we have a hugely precarious labour market, because they have opted for precarious working conditions,” says Sana Mahi Doost.

“This leads to stress, a sense of powerlessness, and a fear of the future. [Education Minister] Søren Pind now says he is concerned that young people is that group in society that is the least happy. This is something we have been saying to different ministers for years, and they have laughed us off.”

But if you think that the ‘68er’s themselves will come to the aid of the students 50 years later, you will be mistaken, according to Doost.

When they passed the Study Progress Reform, the resizing ‘dimensioning’ cuts, the SU study grant reforms, and we stood all alone – where were the ’68er’s then?

Sana Mahin Doost, National Union of Danish Students (DSF)

“I have read a number of interviews on the occasion of the 50 years since 1968, where the ‘68er’s complain that young people are not what they used to be. But you have to ask yourself: Where the hell are the ’68er’s themselves now? They have not managed to continue the fight, even though they had completely different conditions. On the Berlingske news site, they tell us they did not need to enter the labour market. They say: “We could do whatever we wanted, it was so awesome. The young people go to fitness, but we threw off our bra’s.

All those calculations, where you have to ask: What are the conditions from which we have to act under today?”

She says the old rebels have failed their successors.

“I feel ambivalent about 68. The battle they fought was tremendously inspiring, and when we have co-decision making and collegial bodies today, it is because they demanded their rights. And they are the reason why we have universities that are open and not elitist. So they achieved many things that we stand for, and I am pleased about that. But much has since been rolled back, and so we ask ourselves: When they passed the Study Progress Reform, the resizing ‘dimensioning’ cuts, the SU study grant reforms, and we stood all alone – where were the ’68er’s then?”

“The rights they received were for their own benefit, but it is perhaps more relevant to judge a student uprising on what it leaves as collective rights to the next generation. Here, the ’68er’s were not successful, because most of this stuff has been rolled back. Today, when we fight for the study board – which for me is the ultimate symbol of what was achieved in 68 – the ’68er’s do not speak of it on the Berlingske news site, they just point their fingers at the current youth generation. I think: Was this just for yourselves? Have you been too busy with your houses out in Gentofte, and your delightful jobs out in the national broadcaster DR?”

It is hard to imagine a political leader like Sana Mahin Doost without the ’68er’s – and for that matter her partial patricide of them 50 years later. The same cannot be said of law professor – and writer of university history – Ditlev Tamm (born 1945).

Doost calls for a new resurgent set of ‘68er’s in a new form; Tamm blames them for today’s debacle.

He, who himself viewed the events from the sidelines, at the end of his own study period, does not write favourably about the 1968 rector and socialist Mogens Fog, who opened up the doors to the student rebellion at the demonstration of 5,000 people in April 1968. In a review of a book on Fog, Tamm writes: “It was as if the university gave up on fighting for its own values.”

“The stand against the authorities was generally a good thing about the 68 uprising. Unfortunately, today’s old authorities at the university have been replaced by new ones – and worse ones,” says Ditlev Tamm, who himself was given a position at the university as a newly minted lawyer and given the opportunity to see how the new collegiate bodies that arose after 1970 worked in practice. Not very well. Professionalism was supplanted in a struggle for power, and this power was not for building a better university, he has argued.

In this way, according to Ditlev Tamm, the ’68er’s themselves prepared the ground for the present-day rulers – the politicians, officials and hired managers who now reign over what was once a collegially controlled university.

The paradox is that the ’68er’s, by politicising and ideologising the universities in the name of freedom, and by relinquishing their professional basis, planted the seeds of distrust of factual knowledge in society. This broke down the general respect for the university and damaged its reputation. In this vacuum, the politicians took over control, says Ditlev Tamm.

”The

“After that, professors became marginalized and were no longer invited to the university’s annual celebrations. I had to admit that UCPH was no longer my university anymore, as I had known it previously. It had become a university of management with a hierarchy with no sensitivity to employees. The key word is ’employees ‘. I had never thought of myself as an employee, but as a professor in a profession. Part of my motive for becoming a professor was that you were not employed in a subordinate position, but had independent responsibility for your profession.”

But if the spirit of 1968 can be hard to trace today, you can take comfort in the fact that the political battles of the period may not be the ideal prism through which to see things, if you want to lead the development of the universities into a new era.

This is according to professor and director of the Department of Media, Cognition and Communication Maja Horst. Together with CBS Professor Alan Irwin, she has written a book ‘What do we want to do with the universities?’, which includes recommendations for a high degree of autonomy in universities. This sounds a bit 68er like.

“I consider myself a child of the youth rebellion – born in 1969 – and I am very influenced by what happened. But I do not wish to return to the same spirit that prevailed then,” she writes in a mail.

The global challenges of climate, migration and poverty we can only solve if we work together. For this, I do not think 68 really had anything to say. The same goes for the transformation of the academic labour market and the creation of an academic precariat. There I do not think that the spirit of ’68 contributed much.

Maja Horst, Professor and Head of the Department of Media, Cognition and communication, UCPH

“I think it is more relevant to ask what we have gained from the rebellion, which we still appreciate today. And there are many things. First of all, the stand against the authorities and the fact that students and professors now work together, side by side, in the laboratories. Our lack of hierarchy makes us able to be far more creative than many other groups around the world. ”

Maja Horst and Alan Irwin’s book is built up as a debate between two archetypes, the freedom fighters and the society engineers. A debate that, according to the authors, is unproductive.

“The debate has inherited something from the youth rebellion, but not just that. It has many other origins. These positions prevent us from dealing with a lot of problems, challenges and opportunities faced by universities. In this way, it can be said that the ideals of the 68er’s can also stand in the way of innovation. ‘

According to Maja Horst, the world is simply quite different today. She notes (somewhat ironic, perhaps?) that the rebellion of 1968 took place, “when you had .” In some ways the world was more privileged, which may have given the political movement of the present a slightly restricted worldview, and perhaps even made – as Sana Mahi Doost also said – the 68er’s selfish.

“The world today is, first and foremost, more global and hyper-competitive,” writes Maja Horst. “The global challenges such as climate, migration and poverty we can only solve if we work together on them. For this, I do not think 68 really had anything to say. The same goes for the transformation of the academic labour market and the creation of an academic precariat. There I also do not think that the spirit of ‘ 68 contributes much.

The slogans of the demonstrators ‘ banners at Frue Plads in 1968 were on breaking down the professors regime and codecision making now. 50 years later it is not the power of the professors in smoky old boys’ rooms, that the students are trying to cut down. Today, the struggle is between the students and the technocrats in the Slotsholmen civil service buildings, that smiles kindly, but who are contracted to get a return on their SU study grant investments, and preferably fast. Regime of the ministers, no thanks! Reads the headline of a current featured article from the Student Council in 2018. And the co-decision making is looking sad. Not least if the study boards are put into the grave.

There’s no nice way of saying it, but ‘1968’ is just not what it was.